The advantage of using alternative procedures such as metagenomics to pure-culture based studies in microbiology.

The transition away from pure culture to other procedures including metagenomics has three key advantages. First, it enables us to capture a snapshot of community composition which pure culture-based studies cannot do (as the goal of a pure culture is to obtain only one organism). Second, it allows the sequencing and identification of microbes which are unculturable under current conditions e.g. they grow in too low PH or rely on a metabolite produced by the host (syntrophic interaction). Third, it enables a snapshot of the whole microbiome to be taken under a variety of conditions e.g. microbiome with and without a pathogen present which is very difficult to do in pure culture-based studies.

Metabarcoding is the main technique to capture a snapshot of community composition in the plant microbiome. Although there are still some limitations with this (e.g. many fungi in plant microbiome are multinucleate and have variable sequences which make metabarcoding of ITS regions difficult), there has been great success of capturing the bacteria in the plant microbiome using 16s rRNA sequencing. For example, as highlighted in (Bai et al., 2015) metabarcoding of the16s rRNA gene of both the rhizosphere and phyllosphere microbiomes in model plant Arabidopsis thaliana revealed extensive taxonomic overlap between the leaf and root microbiota. The study highlighted that 58% of rhizosphere bacteria share ≥97% sequence identity matches with corresponding 16S rRNA gene fragments of the phyllosphere. Similarly, 48% of phyllosphere bacteria share ≥97% sequence identity matches with the rhizosphere. This is important as leaf and root samples were collected from geographically separated areas (more than 500km apart). This was an example of a finding which could not have occurred (or would have taken a very long time to discover) from pure culture.

Second, many organisms in the plant microbiome remain unculturable in pure culture – largely due to them having syntrophic interactions with their host or other microbes. For example, the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi Rhizophagus clarus HR1 is known to be present in many plant microbiomes. However, it does not have the genes to encode for cytosolic fatty acid synthase (FAS). This means it must rely on plants for some fatty acids which are key to its metabolism – rendering growth in pure culture impossible. However, metabarcoding of the ITS1 region of this mycorrhizal fungi coupled with further ‘omic’ analysis including genomics can reveal its capabilities.

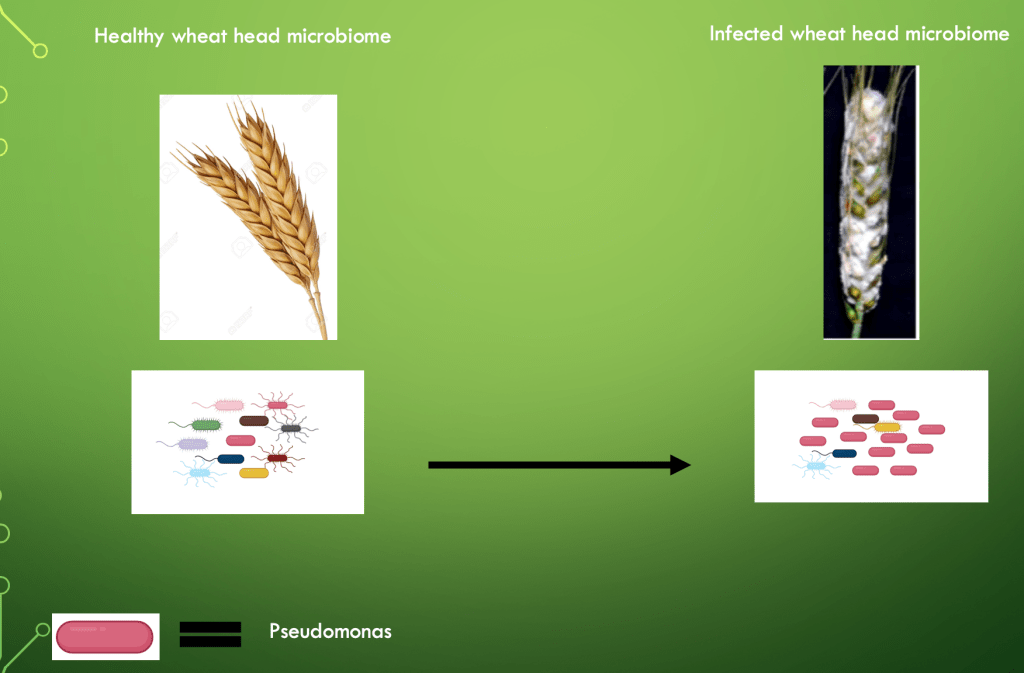

Third, metabarcoding enables us to view how the microbiome as a whole can change in response to a different environmental influence. For example, metabarcoding of the wheat head microbiome revealed that there were significant differences between healthy wheat heads and those which are infected with the fungus fusarium gramarium. Infected wheat heads had an increase in Pseudomonas, paenibacillus and Sphingomonas species, compared to the healthy wheat heads. Notably, Pseudomonas species showed a 10-fold increase after infection. Pseudomonas are known to be antagonistic to fungus. Hence, this establishment of the change in the microbiome composition of the wheat heads could not have been achieved by pure culture. Refer to figure 1.